What a writer does on a snow day

The Midweek Extra Edition of The Upstate American, exclusively for paying subscribers

Message to writers: Don’t shortchange your reading time, and include varied genres.

We were drenched in snow the night before last, a late-winter heavy pileup, and then it snowed some more, until we had probably a foot and a half of snow on level ground by the end of the storm. So we weren’t surprised to hear branches cracking in the woods during the night, or to awaken at dawn yesterday to a house without electricity. The power came back on before too long, but the internet service was out all day. That can be unsettling, you know. Or it can be an excuse for a snow day.

Schools were cancelled and public events postponed throughout the region, but it’s an internet outage that enforces a snow day in our household. And what do writers do on a snow day? We read. Even if it means laying aside chores you really need to do — like writing this (now tardy) newsletter, and meeting a deadline for a radio commentary script — we need to make reading a priority if we hope to fuel the creativity that undergirds our writing.

The promise of this midweek newsletter is to offer you a sense of what lies behind the writing of the latest edition of The Upstate American. As I looked at the essay published Saturday, “Still suckers for giant frauds,” I realized how constantly I draw upon my wider reading as I prepare each weekly report. As a student of American social and political history, I constantly come across useful facts and understandings in my non-fiction reading. But literature provides a different value for a writer: Not only our worldview, but also our creativity, is stimulated by great writing. Our snow day underscored for me an awareness that everything I write, regardless of the topic or the genre, is an outgrowth of what I have read.

Today’s writing tip, then, is simply this: Always be engaged in reading — both fiction and nonfiction — and remember that you’re a quite typical writer if you believe that there are so many other activities that demand your attention first. You’re right in that, but you should read anyway, because writers must consciously and constantly make time for our reading.

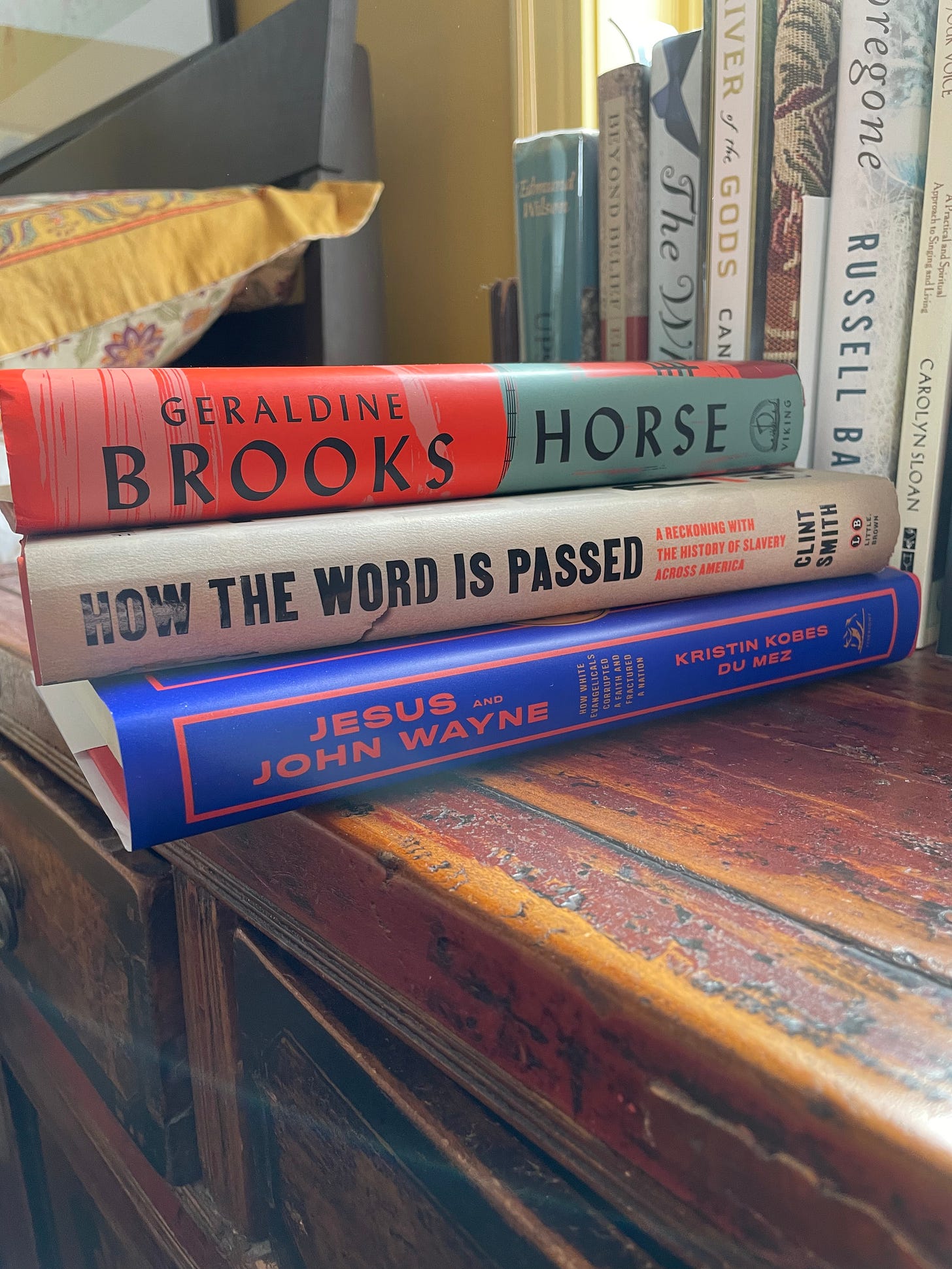

Just now, three books are in the “active” pile on my bedside table — the fine novel Horse published last year by Pulitzer-winning author Geraldine Brooks, and two nonfiction works that explore American history and society. The latter books will be useful as I shape columns in The Upstate American in months to come, because they delve into racism and Christian nationalism, two topics that are quite relevant today. They’re in that category that’s often called “reading for knowledge,” which is the kind of reading that occupies most of us, since it includes news coverage. But fiction carries us beyond that, and it should be a part of every writer’s diet.

In fact, neuroscientists have published research suggesting that literary fiction helps us expand our critical thinking and develop empathy. Those factors make us more fully human, not to mention more open to new understanding — which helps us handle day-to-day realities ranging from hard conversations at work to boring conversations at social events. That makes the reading time a practical undertaking, beyond the fact that it’s simply entertaining.

Case in point: I have just finished Hamnet, a remarkable 2020 novel by Maggie O’Farrell, which is the fictionalized account of the 1596 death of an 11-year-old boy whose father a few years later wrote a quite successful play called Hamlet (the name, O’Farrell notes, being the same in old English as the playwright’s son). I’m always drawn to good historical fiction because it draws me closer to an impossible goal, of grasping a world that existed before my awareness. This book offered a vision of how the life experience of William Shakespeare inspired some of the genius that is obvious in his work. The novel is surely and inevitably not a precise account of what really happened in Stratford more than four centuries ago, but its deeply-researched scenes have changed how I will look at Shakespeare’s work from now on. (Notably, it includes an astonishing omniscient death scene, which is hard to pull off credibly, since writers have experienced only this side of the divide.)

So here’s your midweek advice: If you’re not lucky enough to get a snow day delivered to you from the sky, seize one — or at least a part of one — the next chance you get, and use it to enjoy your reading. Then try to make it a habit, day by day. It will make you a better writer — not to mention someone less likely to be a jerk at work or boring at a social event. Yep: reading can do all that for you.

Thanks again for reading The Upstate American, and for supporting my work exploring our common ground, this great land. And if you’d like to learn how to write opinion essays — for newspapers, audio or digital platforms — check out the class offered by The Memoir Project by clicking below.

-Rex Smith