Where to find comfort from official torment

Our president offers no solace when the nation is in pain. Where do we turn?

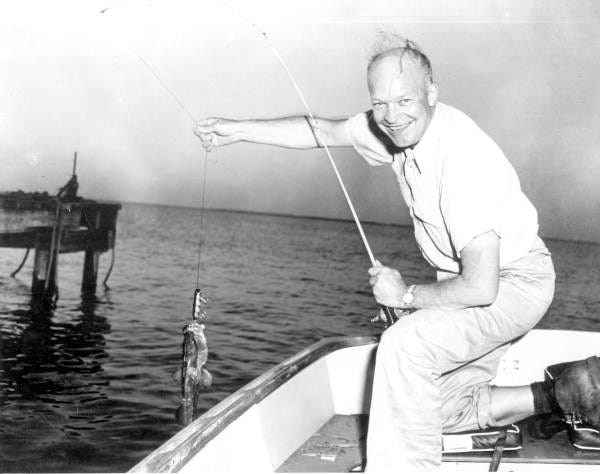

Dwight Eisenhower served at a time when a president was seen as both a moral and a comforting presence.

The first American president to register in my consciousness was born the same year as my grandfather, and I saw the two men as similarly comforting. Like Granddad Smith, Dwight D. Eisenhower projected steadiness and calm. He talked about and promoted peace and prosperity after years of war and economic unease; in the face of challenges to the law, he was resolute about the nation’s principles, including its commitment to equality for all. The quiet assurance that Eisenhower displayed during the days of the Cold War offered inspiration. “We face the threat not with dread and confusion, but with confidence and conviction,” he said.

Presidents of both parties throughout my lifetime have likewise offered comfort when the nation might be wracked by grief or fear, and constancy in the face of unease. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, said, “I need your help — I cannot bear this burden alone,” and asked Americans to “put an end to the teaching and the preaching of hate and evil and violence” by enacting civil rights legislation. In 1982, when a Black family in a Maryland suburb faced racial harassment that included a cross burning on their lawn, Ronald and Nancy Reagan visited their home, the president asserting that modern America wouldn’t tolerate such acts. In 2015, during a eulogy in Charleston for one of nine victims of a church massacre, Barack Obama spontaneously began to sing “Amazing Grace.” The crowed of 5,500 soon joined, in a powerful moment of unity and hope.

How far we have fallen. No one can reasonably view Donald Trump as a man capable of offering comfort to a troubled nation, nor inclined to do so. His response to tragedies instead typically enflames emotions by, first, scapegoating groups or individuals, and then demanding praise for his own behavior.

We’ve seen this show a lot, but it never ceases to horrify. When Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico during Trump’s first term, the president complained on social media that people there “want everything to be done for them,” and later griped that the estimated death toll of almost 3,000 “was done by the Democrats in order to make me look as bad as possible.” As Covid-19 bore down on the United States, Trump focused on blaming China but insisted that it wouldn’t cause problems in America; during Covid briefings, a Washington Post analysis found, he spoke 13 hours, mostly praising himself and his administration and devoting only 4.5 minutes to condolences. A Columbia University study of his botched response estimated that if the Trump administration had followed the course of other wealthy nations, as many as 210,000 Covid deaths could have been avoided.

Even by those standards, though, the president’s behavior in the face of recent tragedies has been especially unsettling. He blamed “a radical left group of lunatics” for the killing of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk. He stopped all migration from “third-world countries” — a category not recognized in U.S. law, but which he quickly applied to 19 nations — when an Afghan immigrant shot National Guard troops in Washington, D.C., as though an entire migrant group was guilty of the crime. Last week, after two Brown University students were killed, Trump blamed the university for having too few security cameras (there are 1,200), then suspended a green card lottery program that the suspected killer, a Portuguese citizen, had used to enter the U.S. eight years ago.

Perhaps most egregious was Trump’s response to the murder of Hollywood legend Rob Reiner and his wife, Michele. Trump quickly used a social media post to blame Reiner for his own death — claiming it was “reportedly due to the anger he caused others through... a mind crippling disease known as TRUMP DERANGEMENT SYNDROME.” When even many Republicans expressed concern about the tone, Trump doubled down, claiming Reiner was “deranged.”

Maybe it was always unrealistic to expect a president to be the nation’s consoler-in-chief. Perhaps the displays of consolation by previous political leaders were mainly performative; Trump aides suggest we’re better off with a leader who gives us his real self, even if he sometimes offends.

Or maybe, in any case, we need to develop more skills to console ourselves. The years ahead are likely to include plenty more moments in which our nation’s arrogant leader will display the characteristics of the so-called “dark triad” traits of narcissism, psychopathy and Machiavellianism. So perhaps our task is to do what we can in our own environment to counter the damage of Trump, and thereby sustain others and ourselves through the storm.

Empathy is a crucial human skill that is needed to build relationships and sustain compassion. Psychologists have long considered empathy to be a core emotion that helps differentiate humans from other species. Even toddlers display empathy, but it is a trait that can be developed — or, like a muscle, it can atrophy from disuse.

But empathy is now out of vogue on the political right. We’ve heard Elon Musk’s claim that empathy is “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization,” and JD Vance’s odd notion that Catholic theology places an order on empathy’s application, with foreigners far down the list of those deserving care. Key leaders of Christian nationalism, the political movement at the heart of Trumpism, have asserted that empathy can be sinful — “an artificial virtue,” in the words of Southern Baptist Seminary president Albert Mohler, since “the whole impulse of empathy is feeling with people as they feel,” when their religion demands less nuance in judging right from wrong.

Yet empathy seems so needed now, as we recognize the disconnect that is plaguing Americans. That was so even before the brutality of recent days — before people were gunned down on American campuses, before Australian Jews were slaughtered on a beach while celebrating the first night of Hanukkah, before a beloved American entertainment star and his wife were murdered by their troubled son. We were already frayed by the constant onslaught of news from Washington that is mighty tough to accept: health bureaucrats putting children’s lives at risk by disregarding scientific standards, politicians blithely ignoring the need to keep healthcare available to people without resources, American missiles blowing people out of the sea in a show of force seemingly aimed at taking control of rich Venezuelan oil fields.

To many of us, this seems to be a moment of not just political upset, but of moral crisis. The Trump ethos is challenging ethical standards that have been fundamental to Americans for generations, putting two questions before us: What are we to do, and where might we find comfort?

The answer to the first question is easier to imagine, though not to execute: We must each do what we can to help our society return to a better course. John F. Kennedy was prone to quoting Dante: “The hottest places in hell are reserved for those who, in time of great moral crisis, maintain their neutrality.” The moral crisis in America is now driven by its political culture, so a solution requires political engagement. Among those who are able, standing aside is an immoral choice.

As to comfort from the pain of this crisis — from the daily onslaught of bad news, and the knowledge of what is being done by careless leadership of a government that acts in our name — the solution clearly won’t come from the top. It’s up to each of us.

Comfort can first come, certainly, from human connection, if we are fortunate enough to have it — from family and friends. It can come from activities that give us meaning, including art and music and engagement with nature. Some people find comfort in their work, which can be engaging and filled with purpose. Often comfort comes from simple pleasures, of course: a warm cup of cocoa, the soft ear of a dog, the scent of a flower, the smile of a child.

But in a time when so many people are feeling the pain of disappointment, disenchantment and loss — when our hearts are broken by the carelessness and heartlessness of actions in our own nation’s name — there’s a good chance that we might find comfort in extending it to others. It’s useful to recall the elegant phrasing of William Wordsworth, the romantic poet of England who was coming of age as our American government was taking shape: “Look at you comforting others with the words you wish to hear.”

Mental health researchers have consistently documented the health benefits of reaching out to help others: better mood, higher self-esteem and greater life satisfaction. It’s partly attributable to the release of the so-called “feel-good” chemicals in our brain — serotonin, dopamine and oxytocin — that both create more resilience and make us want to repeat the activity. It’s a natural cycle that expands the reach of kindness by encouraging its repetition.

The findings suggest that the best course when we feel most shaken is not to retreat, but to engage: to draw upon that admirable human quality of empathy. The very targets of the Trump administration’s malevolence are the places and people we might extend our hands to help, aiding ourselves in the meantime.

There will come a time, surely, when America will again be led by a person of high moral character and integrity — someone like Dwight Eisenhower, who in his final address as president urged the nation to be “unswerving in devotion to principle, confident but humble with power,” to yield a world in which the greatest and poorest of nations could join in “a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.”

That’s not the world of now, but with our individual efforts, we might find comfort in knowing it yet can be our future.

START THE NEW YEAR WITH A WRITING INITIATIVE

LEARN TO WRITE OP-EDS — FOR PRINT, AUDIO AND PODCASTS

If you’d like some training in writing opinion essays — for newspapers, audio or digital platforms — check out the live 90-minute class Rex co-teaches that is offered by Marion Roach Smith’s global platform for writing instruction, The Memoir Project. Click below for information on our upcoming schedule of classes.

Our next class is TUESDAY, JAN. 13 at 1 p.m. Eastern.

Why not join us?

Lots of our students have been well published — and you can be, too!

BONUS CONTENT

GET MORE FROM THE UPSTATE AMERICAN

IF YOU’D LIKE TO HEAR MORE from Rex Smith, check www.wamc.org for his weekly on-air commentary aired by Northeast Public Radio. Here’s a link to the latest essay, which is an earlier version of this week’s column, adapated for audio.

AND IF YOUR INTEREST IS SPECIFIC TO AMERICAN MEDIA, you can download the podcast of The Media Project, the 30-minute nationally-syndicated discussion that Rex leads each week on current issues in journalism. In the seven states where Northeast Public Radio is heard, the program airs at 3 p.m. each Friday and is rebroadcast at 6 p.m. Sunday. You can tune in live, too, at www.wamc.org, or download the podcast there. It has been called “a half-hour of talk about finding and telling the truth.”

THANK YOU for reading The Upstate American, and for joining us in the conversation about our common ground, this great country. As we together navigate these challenging times, I hope you’ll join us again next week — or send me a message with ideas you’d like to see us address. I love to hear from readers.

TO ALL, in this final post of 2025, I wish you a very Merry Christmas, and a season of light and hope.

-REX SMITH

"Let the beauty we love be what we do. There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground." - Rumi

Thank you for this inspiring essay, Rex. Peace to you and yours this holiday season!