How to save America's golden age

Athens and Rome once led the world, but their time passed. Has ours, too?

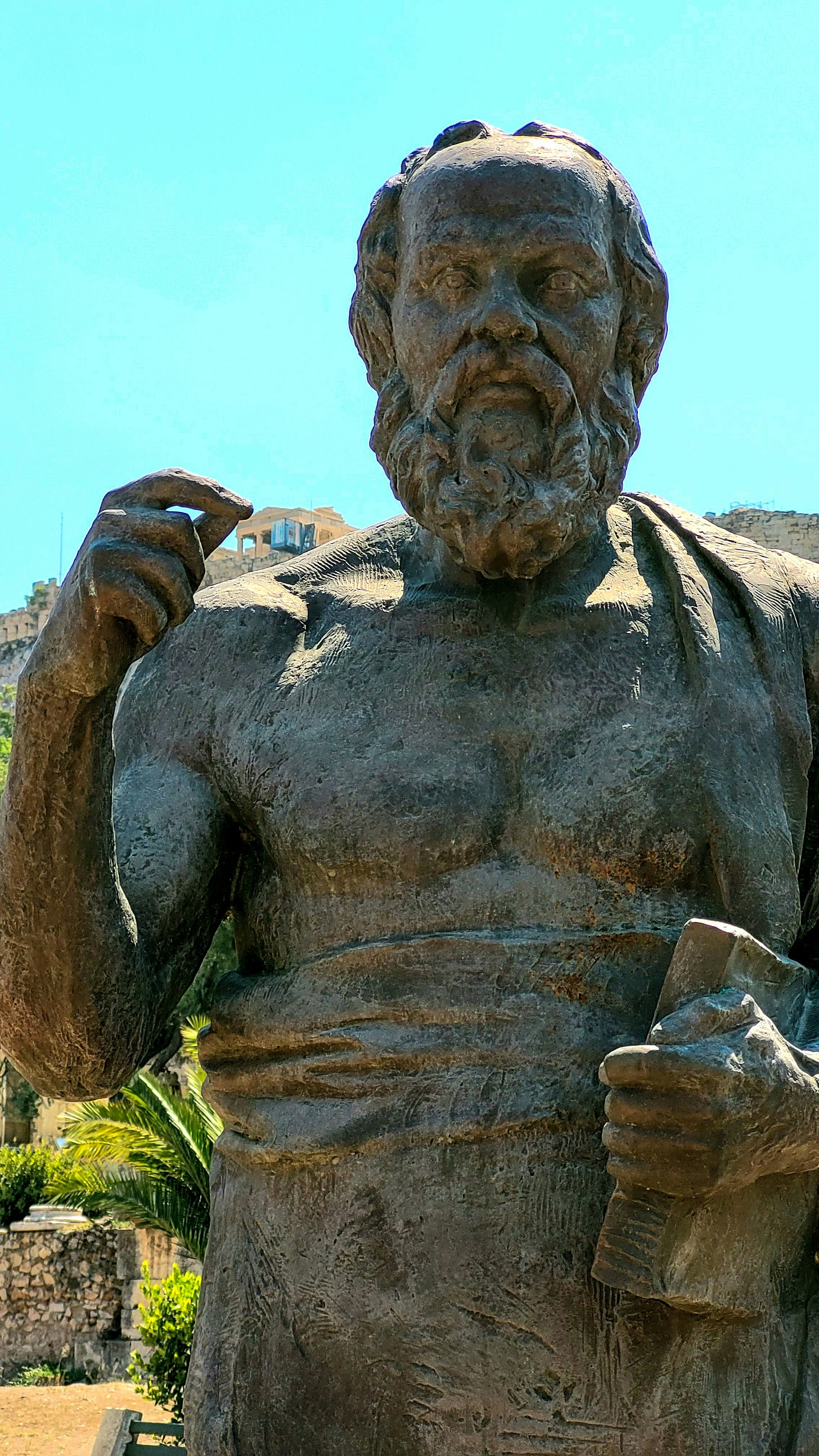

“Let him who would move the world first move himself,” wrote Socrates. (Photo by Felipe Pérez Lamana on Unsplash)

Travel presents the chance to leave behind daily worries, and a look at the shelves of airport bookstores suggests that lots of travelers buy reading to meet that opportunity: Mostly, it seems, the market demands entertaining stories by popular authors – thrillers, mysteries and romances. They’re like burritos from Taco Bell: cheap and fast, good enough on the run, but not what you want for long-term sustenance.

My travel reading is more aspirational, like Michelin-star dining for the brain. So on an extended trip last month, I once again picked up a 500-page history, imagining, as I often have, that I would use the moments between adventures on the road to make up for what I’ve failed to learn in the decades before now. This hope for a sort of remedial learning is rarely realized; usually there’s too much to digest outside to take time on the road chewing so much substance.

But I have kept reading the fat volume I picked up on our recent trip’s first day, and it has delivered a sense of a key factor underlying both America’s current peril and what may be needed to overcome it. Or, less hopefully, a view of how our society is indeed likely to slip into further decline. Johan Norberg, a Stockholm-born historian, was clearly motivated by just that concern in writing Peak Human: What We Can Learn from the Rise and Fall of Golden Ages.1

Norberg writes of the places and times that dramatically surpassed their surroundings and contemporaries: of Athens, where both philosophy and the concept of democracy took shape, and Rome, which dominated the western world for five centuries; of the hundreds of years when Islamic Baghdad was the center of learning, culture and trade; of Renaissance Italy and the British Empire, of course, and more. Those societies dominated their times, Norberg writes, until they eventually lost their way and failed.

In each case, he notes, the decline happened when the societies succumbed to what he considers civilization’s worst enemy: fear.

“Again and again, we see civilizations prosper when they embrace trade and experiments, but decline when they lose cultural self-confidence,” he writes. “When under threat, we often seek stability and predictability, shutting out that which is different and unpredictable. Unfortunately, this often makes the fear of disaster self-fulfilling…” because, he notes, “The problem with paralyzing fear is that it has a tendency to paralyze.”

For a nation that has long based its identity on its sense of promise and its growth and achievement, it is devastating to think that it all may be slipping away. Donald Trump tapped that fear in promising to “Make America Great Again,” which makes his callous disregard of the Constitution and political norms all the more shocking. A confident nation can do big things: eradicate slavery, rise from the Great Depression, land men on the moon, shape a Great Society. Those accomplishments were not achieved without fear, but by overcoming it.

It’s not so much that fear makes great societies crumble in the face of lesser adversaries, Norberg writes; rather, they are brought down by the fear generated by clashes within. “Every culture, country and government is capable of decency and creativity,” he writes, “and of ignorance and jaw-dropping barbarianism.”

If you doubt that America has swiftly slipped from its golden age into the latter category, consider the examples of ignorance and barbarianism around us: Before the United Nations, our president denounced “the global warming hoax,” labeling scientists’ warnings about climate change “the greatest con job ever perpetrated on the world.” His top health official, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., fired the government’s top vaccine experts, cancelled research into infectious diseases and is spreading scientifically debunked claims about autism. Those are ignorant responses to the fear of change or uncertainty.

As for barbarianism, U.S. military forces have recently killed at least 27 non-combatants in Caribbean waters, in apparent violation of international law, even as masked paramilitary forces are seizing civilians on our nation’s streets amid dubious claims of an invasion by Latin American drug gangs.

Norberg’s review of history reminds us that concerned Americans are in good company in recognizing that these responses present a threat to the nation’s achieved glory; many in Athens and Rome saw it coming, too, as their societies crumbled. Yet in analyzing how great civilizations rose and fell, there are paths that offer hope for sustaining America’s own golden age. They’re found in the capacity to overcome fear.

The notion of American exceptionalism — that this nation is unique in the world, and its success is a result of God’s will – has long been pedaled by nationalistic cheerleaders, and it has taken hold in many quarters. A 2021 study by Public Religion Research Service sought to learn whether Americans agreed with the notion that “God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world.” The poll showed that only 30 percent of all Americans share that view, but it drew agreement from a majority of Republicans, white evangelical Christians and people who said they trust Fox News. That’s Donald Trump’s political base, and the core that motivates Republican lawmakers to stick with him to avoid their own political demise.2

If you believe that God ordained the nation’s founding and willed your forebears to subjugate the land’s indigenous population, it’s not hard to embrace the idea that it’s likewise your calling to suppress challenges to that holy charter — to cleanse the country of imagined invaders and internal enemies, and to defend those who, like you, claim to operate under God’s aegis. Elites throughout history, backed by the masses under their influence, have sought to kick away the ladder that raised them to success and push off challengers, both within and from outside.

Immigration is an especially pesky problem for successful civilizations. “Being open to the contributions of other civilizations is the quickest way of making use of more brains,” Norberg writes. Yet immigrants instill fear of replacement among incumbents, so their contributions are often stifled, leading civilizations to turn inward and lose the inspiration brought by unfamiliar encounters.

That’s just where America finds itself now, of course. Donald Trump drew his initial support from people who imagined that their opportunities had been siphoned away by people unlike themselves — by non-white citizens, immigrants, coastal elites and the 38 percent of adults who have a college degree. Trumpism was powered by the fear of losing ground to those people, and that fear sustains him today.

Yet if it is fear that motivates Trump’s base, it is likewise fear that limits the response of his opponents. In his second term, Trump is maximizing his power to instill fear based upon what might happen to those who stand in his way.

There’s reason to be afraid, of course. One institution after another has caved to Trump’s pressure for fear of what he might do if they don’t: He could pull billions of federal research dollars from universities, hobble major law firms by withdrawing their access to federal information, destroy the business models of media companies by blocking mergers, and create regulatory roadblocks that could weaken technology firms.

Nor are individuals free of the fear of crossing Trump’s agents: Prominent people have faced selective prosecution and federal workers’ careers have been ruined; ordinary folks have been targeted for online harassment and physical violence based on what they have said or published. Vice President JD Vance said that people who criticized the late right-wing provocateur Charlie Kirk ought to be reported to their employers — suggesting that anybody who disagrees with the administration ought not to have a job.3

Beyond that, in some circles there is fear that not supporting Trump puts a person at risk of social isolation. There are 444 counties in the United States designated by the Agriculture Department as “farming-dependent,” and Trump carried all but 11 of them in 2024. So it’s hard to be a Trump critic in rural America. The same is true among young men: 56 percent of male voters under age 30 supported Trump (compared to 40 percent of young women). You’ve got to stick with The Man to be a bro.4

And there is, of course, the most elite fraternity in the country, the United States Congress: Among its 535 members are 272 Republicans, and surely there are a few, at least, whose conscience is troubled by what’s going on. Yet barely a peep of disagreement is ever heard, because The Boss won’t tolerate it.

Fear is degenerative to our society and ultimately can be destructive of our golden age. We are therefore called to disable it.

While history reveals the tragedy of societies that were attacked by fear and succumbed to its poison, it is also filled with stories of generations that have thrived thanks to the courage of those who stand up to be counted.

We are of course indebted to those who laid down their lives for freedom. Some years ago, on an anniversary of the D-Day invasion, I stood on what we know as Omaha Beach, just over the cliff from the graves of more than 9,000 Americans who died during the invasion and the fight to liberate France from Nazi control. On that sunny day, I silently promised those lost souls that I would never take for granted what they bequeathed to us.

Few of us make such a sacrifice, but we all have opportunities to display courage in the context of our time and place. The eminent historian Timothy Snyder, in his essential volume On Tyranny, notes that sometimes it is our physical presence that is needed — because “nothing is real that does not end on the streets.” Most people who read this edition of The Upstate American will do so as No Kings Day protests are scheduled to take place across the country — the type of activity that is important because, as Snyder writes, “If tyrants feel no consequences for their actions in the three-dimensional world, nothing will change.”5

Yet the courage of visible resistance to oppression must be coupled with a broader courage — that represented by a society’s openness to change and new ideas. That is why we today remember Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Starting in about 600 B.C., their Athens was the site of an explosion of creativity and growth, in no small part because of its citizens’ self-confidence. “It was made possible by a very unusual openness to innovation and surprises from abroad and within,” Johan Norberg writes.

America’s confidence throughout its history has sprung from its ideals and its successes. We were blessed with vast natural resources, a brilliant constitutional heritage and generally good leaders, and at crucial times our people have risen to embrace hope and to welcome innovation. Most of those assets remain with us today.

What we need, it seems, is the courage to reassert our will over those who would consign us to the ignoble sharing of their fear. To save this golden age for generations yet to come, then, we need to summon that courage and display it daily. That’s the key to rebuilding the courageous capacity of our whole society.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd. Norberg is a senior fellow of the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.

https://religionnews.com/2021/10/12/survey-christian-nationalist-view-of-history-correlates-with-support-for-racist-conspiracy-theory/

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cz0x4e3zn2jo

https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2025/06/26/behind-trumps-2024-victory-a-more-racially-and-ethnically-diverse-voter-coalition/

Originally published in the United States in 2017 by Tim Duggan Books, an imprint of Random House.

TRAINING

DO YOU WANT TO LEARN TO WRITE OP-EDS?

If you’d like some training in writing opinion essays — for newspapers, audio or digital platforms — check out the live 90-minute class Rex co-teaches that is offered by Marion Roach Smith’s global platform for writing instruction, The Memoir Project. Click below for information on our upcoming schedule of classes.

Our next class is Wednesday, Nov. 19, at 6 p.m. Eastern. Why not join us?

Lots of our students have been well published — and you can be, too!

BONUS CONTENT

GET MORE FROM THE UPSTATE AMERICAN

IF YOU’D LIKE TO HEAR MORE from Rex Smith, check www.wamc.org for his weekly on-air commentary aired by Northeast Public Radio. Here’s a link to the latest essay, which is an earlier version of this week’s column, adapated for audio.

AND IF YOUR INTEREST IS SPECIFIC TO AMERICAN MEDIA, you can download the podcast of The Media Project, the 30-minute nationally-syndicated discussion that Rex leads each week on current issues in journalism. In the seven states where Northeast Public Radio is heard, the program airs at 3 p.m. each Friday and is rebroadcast at 6 p.m. Sunday. You can tune in live, too, at www.wamc.org, or download the podcast there. It has been called “a half-hour of talk about finding and telling the truth.”

ENDNOTE

THANK YOU for reading The Upstate American, and for joining us in the conversation about our common ground, this great country. As we together navigate these challenging times, I hope you’ll join us again next week — or send me a message with ideas you’d like to see us address. I love to hear from readers.

-REX SMITH

Two quotes come to mind:

“The world is full of people whose notion of a satisfactory future is, in fact, a return to the idealized past.” - Robertson Davies

“If you want something new, you have to stop doing something old.” - Peter Drucker

We must make a new future, not an old one.

Excellent article, well written. Scary as well.