It sounded bad back then, too

Political campaigning is relentlessly negative nowadays -- but it was never pleasant

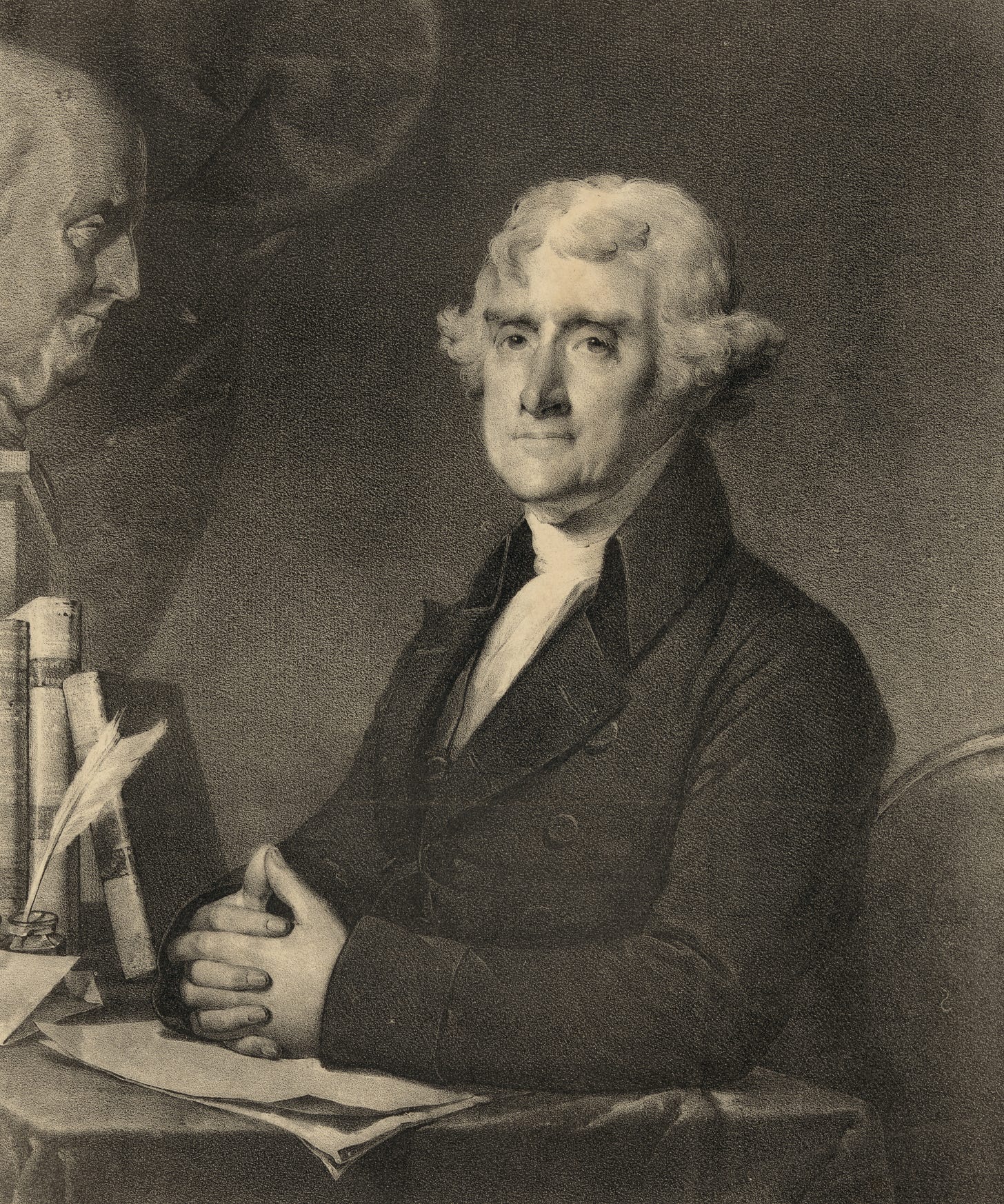

Jefferson’s presidency defied his foes’ prediction of doom. (Photo by Library of Congress on Unsplash)

My neighborhood is toast, it seems, no matter who wins the race for Congress in our district this year, because both candidates are said to be “dangerous” — one because he is a sympathizer with communist China, the other because she betrays cops, FBI agents, and veterans when it’s politically convenient. I’m just going by what the ads for each side tell us about the other candidate, you know, but surely somebody who wants me to trust them with my vote wouldn’t lie to me. Right?

I know that I should look into this myself, but I’ve been busy trying to track down the local Death Panel that was set up under Obamacare. What’s that? There are no Death Panels? But the ads during the mid-term campaigns a dozen years ago said they were coming. You mean political ads sometimes aren’t true?

There’s always a temptation to conclude that the present is unprecedented, but it seems accurate to say that nobody alive has experienced political discourse quite as vicious as it is just now. Lying is endemic among Republican candidates, most of whom back the flat-out falsehood that the 2020 presidential race was stolen. But attack advertising is bipartisan. Right now, running for office is less about explaining a candidate’s stances than trashing an opponent’s reputation.

There are reasons why this is happening, and there are consequences that nobody welcomes. But it will be hard to reverse the downward spiral of American politics. It is a dispiriting notion among many as the campaigns of 2022 come to an end.

Yet we may take some comfort from our history, which reveals quite a record of political invective. Consider 1800, when two of the august founders of our republic, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, squared off for the presidency: Adams, the incumbent, was said by Jefferson partisans to be a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” But if Jefferson was elected, Adams’ advocates averred, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest, will openly be taught and practiced.”1

History does not record an upswing in the advocacy of adultery and incest after Jefferson’s victory, but the Adams family seemingly maintained its embrace of negative campaigning: In the next generation, supporters of incumbent John Quincy Adams trumpeted the notion that his presidential challenger, Andrew Jackson, was a bigamist. That was true, sort of: Jackson’s wife, Rachel, had married him in the belief that her first husband had obtained a divorce; when she discovered that he apparently had not, the Jacksons remarried after the divorce was finalized (long before the presidential race). Anyway, to voters in 1828, bigamy seems not to have been a disqualification: JQA became a one-term president, like his father.2

Indeed, negative information doesn’t always dissuade voters, as the case of another one-term president, Donald Trump, suggests. He was elected despite credible allegations of sexual misconduct against him raised by 19 women. Would it have made any difference if that had been stressed by his 2016 opponent, Hillary Clinton?

Maybe so, because it’s an unfortunate fact that the “attack ads” that permeate campaigns these days usually do their job. Research at the intersection of psychology and political science has explored why people come to believe what they do in public affairs. One conclusion: It often starts with the so-called “negativity bias” of the human brain. As psychologist Rick Hanson notes, “The mind is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positive ones.”3

To be clear: There’s a difference between focusing voters’ attention to, on the one hand, areas where their views or needs may diverge from a candidate’s stances and, on the other hand, attacking purely to undermine voters’ views of an opponent’s character. For example: Herschel Walker’s demand for a rigid federal prohibition of abortion rightly ought to be viewed against his support for the abortions of women he impregnated, and his scolding of Black men for abandoning their families should be seen in light of his refusal to acknowledge for years some of the children he had fathered. That’s not the same as, say, a counter-factual claim that a moderate Democrat is actually a socialist.

Yet campaign consultants, the professionals who mostly call the shots in American politics, know that once a notion is absorbed from a negative message, it’s harder to dislodge than if the first message is positive — because negative information tends to be “stickier” for most folks.

“Indeed, it is disconcerting to realize just how easily — and deeply — misinformation can lodge in people’s minds, often with a partisan bias,” University of California at Davis psychologist Alison Ledgerwood and political scientist Amber Boydstun have written.4

Media coverage also encourages negativity, since attacks draw more attention. That’s not only true in America, where fact-based journalism now has to compete with partisan pretenders. It’s a reality in every democracy, since there has been a “worldwide proliferation” of negative campaigning, University of Vienna researcher Martin Haselmayer has noted. “Communication research attests that the presence of negativity or conflict increases the ‘newsworthiness’ of stories and events with journalists reporting more on negative news,” he explains.5

In this country, political dialogue has surely grown more coarse in recent election cycles, just as interactions throughout society have grown more rude. Politicians once checked their attacks because they assumed that voters were turned off by negativity — that people wanted leaders of character, the sort of folks who would rise above nastiness. That has fallen out of favor in part, surely, owing to the observable success of Donald Trump, the most boundary-breaking candidate in American history.

Political professionals still offer some caveats — suggesting that there are limits to going to the dark sides of campaigns. Candidates who seems to be cruising toward a win can afford to stress positive messages, and avoid the risk of being perceived as petty and mean. Negative messages don’t sway voters away from their partisan allegiances, though research suggests they may pick off a few genuinely undecided voters. Most significantly, attack ads energize candidates’ supporters, and tie them more tightly to their side.

So it’s more often challengers to incumbents who quickly turn to attack ads, because that’s the quickest way to get noticed. As a young man, I worked in politics before turning to a career in journalism, and I’ve never forgotten what a longtime campaigner told me was an axiom of politics. “You don’t powder puff an incumbent out of office,” he said, implying it was one of those lessons that was engraved on the stone tablets of politics.

The greatest value of negative campaigning, sadly, is likely to lie more in the long haul than in the immediate, as the UCDavis researchers Ledgerwood and Boydstun have noted. That’s because once an idea is lodged with negativity, they write, “it is very difficult to shift perspectives, yielding entrenched attitudes.” Labeling all Democrats as socialists, or all Republicans as radicals, can carry forward among voters for years to come.

Which is what makes the proliferation the attack mode in campaigns nowadays particularly troubling: It seems likely to further cement the polarization that makes progress in government so difficult, as it builds a sense on both sides of the political divide that those other people aren’t trustworthy or deserving of compromise.

If there’s any comfort to draw from the state of political campaigns in 2022, then, it may be in recognizing that this is far from the first time in American history that our political dialogue has been dark and venomous, and that we have survived those days. After all, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson famously reconciled after their bitter divide, remaining the best of friends and dying within hours of each other on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.6

Of course, they were both dedicated to preserving American democracy — which isn’t the priority of many candidates who will assume office soon. If that seems too negative a view at the conclusion of a discussion of how negativity harms our political discourse, I can only suggest that it is frankly true, if harsh. And it is only by depending upon truth that we will be able to find a path forward through the attacks that seem to put our political progress at risk.

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/12487/adams-vs-jefferson-birth-negative-campaigning-us

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/rachel-jackson-was-original-monica-lewinsky-180963713/

https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/the_neuroscience_of_happiness

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1948550617733520

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41253-019-00084-8

https://www.historyhit.com/the-friendship-and-rivalry-of-thomas-jefferson-and-john-adams/

NEWSCLIPS FROM THE UPSTATES

Dispatches from our common ground *

Wherein each week we look around what we call the nation’s Upstates — those places just a bit removed from the center of things — to find illuminating news and intriguing viewpoints, which you might not otherwise see.

This week, we share reporting published here:

Montgomery, Ala. (Montgomery Advertiser, montgomeryadvertiser.com)

Redding, Calif. (Redding Record Searchlight, Redding.com)

Bloomington, Ind. (The Herald-Times, heraldtimesonline.com)

Hanover, Mass. (The Patriot Ledger, patriotledger.com)

NOTE: The complete “Newsclips from the Upstates” section is available only to paid subscribers. Thanks for your support!

ALABAMA

New names coming for schools

In the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd, institutions named for Confederate heroes are being renamed nationwide — but in Montgomery, the process has taken a lot longer than school officials at first promised, according to reporting by Jemma Stephenson in the Montgomery Advertiser. Now, officials are promising that Robert E. Lee High School and Jefferson Davis High School will be renamed by December. Citizen input has been solicited, with the leading candidates including naming the schools for a road one school is located along and for a physician who treated people injured by police attacks during the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery march.

CALIFORNIA

County clerk, right-wing activists on election collision course

Shasta County is in a remote part of California, and Republicans outnumber Democrats almost 2-to-1. That wasn’t a problem until Donald Trump’s false claims that he was cheated out of re-election energized local right-wing activists, setting the stage for a confrontation during the June 7 primary vote count. Now, according to reporting in the Redding Record Searchlight by Damon Arthur, the county clerk is vowing to summon police if citizens display the same sort of “aggressive and inappropriate” behavior. Registrar of Voters Cathy Darling Allen said her office has conducted fair and transparent elections for "the last, five decades, without help from folks who may be well meaning but are not executing that in a way that is helpful." What has changed in recent years is the people who lose elections are no longer willing to accept the results, she said.

INDIANA

Company building homes from straw, mud and limestone

Using robots, a southern Indiana company is building homes from a mix of straw, mud and limestone — with the hope that it could help solve the nation’s affordable housing crisis. A story in The Herald-Times by Laura Lane explains that Terran Robotics is using a $256,000 National Science Foundation grant, with another $50,000 from the state of Indiana, to test a new process for building adobe homes. The idea is to cut the main cost of housing construction, which is labor. Terra's mission statement consists of eight words: "Turning dirt into affordable, sustainable, comfortable, beautiful homes."

MASSACHUSETTS

Church members pitch in to help unexpected migrants

The abrupt arrival of nearly 100 migrants in communities along the South Shore of Massachusetts has prompted the First Congregational church of Hanover to step forward with help. Among the displaced people, according to The Patriot Ledger of Quincy, are Haitian migrants who fled violence and poverty in their home country, and many are undocumented immigrants who speak little or no English. So church parishioners are pitching in to make meals and provide transportation and such needed products as diapers. “Jesus didn’t feed people based on their life circumstances, Jesus fed people because they were hungry,” said the Rev. Peter Johnston, pastor of the church.

ENDNOTE 11.05.22

An election is one step

For candidates, campaign workers and citizens weary of politicking, Election Night is a culmination: all the sweat and effort comes down to who voters select to represent and lead them for the next term of office. For some of us, it presents an opportunity for rest and reflection; for others, it is the beginning of a new adventure. Of course, since many candidates and their supporters this year are suggesting they won’t honor the election results if they don’t win — what unpatriotic claptrap is that! — this may be less of a cessation of hostilities than just another chapter in the fight to sustain the republic.

In any case, an election is really just a way station on the path of democracy’s progress. In any era, there are elections that make us feel hopeful and others that cause us great worry, those where triumph is sweet and others where loss is stinging. Because politics is so fraught in America nowadays — so distorted by lies and misunderstanding, and hobbled by partisanship in pursuit of power — Tuesday night will likely be unsettling for many of us.

We can all benefit, however, if we view the results in the context of the breadth of this nation’s 246-year history. There have been so many elections, and so many times when the Americans who came before us were likewise troubled or exhilarated by the results of voting — which is a comforting notion, I think. We honor those who didn’t turn away from their responsibilities as citizens, win or lose, who stayed in the arena to sustain the effort toward forming a more perfect union. We can’t disappoint those who came before us by abandoning the work now, whether our inclination is to give up in despair or rest on our laurels. That’s not how democracy works. It needs us, not just in this campaign season, but in whatever follows, too. We need to keep hope alive.

Thank you for joining me on this journey on *our common ground, this America.

-Rex Smith

@rexwsmith