They've got to be carefully taught

Lessons to learn from Muhammad Ali and the tragedy in Minneapolis

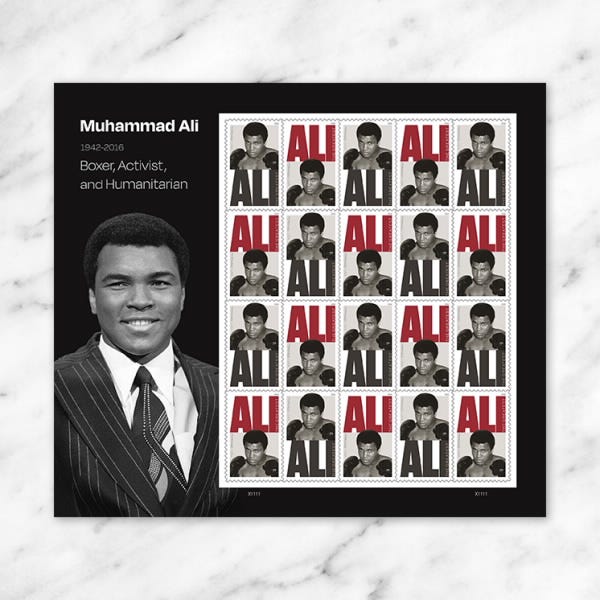

From being prosecuted by the government to being honored by it, Muhammad Ali has emerged as a figure who earned our respect. (USPS image)

The clerk at a post office near our place, a crewcut guy in his 50s, was less than accommodating last weekend when the guy ahead of me in line seemed befuddled, maybe by a language barrier. It wouldn’t have taken any more effort to be kind, I thought. And then I noticed that the customer was nonwhite.

We were in line to send a package, but my wife pointed to a poster showing new stamps — three varieties, featuring winter landscapes, the lunar new year, and Muhammad Ali. “Why don’t you get some of those?” she said, pointing to the smiling face of a young Ali. The poster identified him as “Boxer, Activist and Humanitarian.”

When I asked Crewcut for the Ali stamps, he snorted, “Cassius Clay.” It took me by surprise; I hadn’t heard that name in years. When I didn’t respond, Crewcut went on, “He took the new name when he became —” and here he made air quotes with his hands — “Muslim.” He added, “So he could dodge the draft.”

Maybe I should have just ignored him, and his invocation of a six-decade-old slur on an American who came to be viewed as a beloved symbol of courage and peace. But just now I’m in no mood to tolerate any measure of rudeness by a federal official. “Actually, I think he was pretty great,” I said.

“Yeah, heavyweight champion,” Crewcut said, poking around for my stamps. “What’s not great about that, right?” The Ali stamps were sold out in his spot, and next to him, too, where the clerk was a black woman. I wondered if his anti-Ali commentary was really aimed at her.

“Yeah, that,” I said, as he finally found Ali stamps at a third station, and I found my outrage. “But they took away his championship because he spoke his conscience,” I said. “It was brave of him to do what he did then. Not popular, that’s for sure. But he wasn’t the kind to stay quiet.” Nor could I be at that moment.

Crewcut rang up my sale without further comment. I wonder if he would have had anything to say if I had instead bought one of the new stamps commemorating Jimmy Carter, maybe, or William F. Buckley Jr. — guys who, you know, looked more like him and me. I took my stamps and started to head out, but I couldn’t resist adding, “I think Ali was a man of integrity.”

As it turned out, my little encounter with a federal official came at just about the same time as other agents of the United States government — those commissioned by the president, no less — were firing bullets repeatedly into the back of Alex Pretti, a nurse who had shown up with his cellphone to record what they were doing in the streets of Minneapolis. They killed him as he protested the indiscriminately vicious exercise of police power that has led to the jailing of thousands of people, including some U.S. citizens, immigrants legally in this country, protected refugees, and children.

No, my little encounter with a racist postal clerk doesn’t compare to the killing of Alex Pretti, nor was my dialogue as brave as what Pretti was doing when he died. But as I left the post office, a reality struck me: Ali’s refusal to fight in Vietnam, which led to his banishment from boxing, occurred almost six decades ago — which was surely before Crewcut was old enough to be aware of it firsthand. So his denigration of the man had to be a result of learned bigotry.

There’s a lot of that going around. You could argue that it cost Alex Pretti his life. And unless we face down the generational bigotry and willful injustice that propelled federal troops into the streets of Minneapolis — which I’d wager is exactly like what prompted an Upstate postal clerk to slur Muhammad Ali for an act of conscience so long ago — we will have more bloodshed, more tragedy, in generations to come. This can’t go on. We must be strong in combatting it.

We are divided by politics and prejudice, not by science: Any two humans share 99.9 percent of their DNA, regardless of race, and all humans have a common ancestor, who lived in Africa between 150,000 and 300,000 years ago. So separation by race is a choice, not a genetic inheritance.1

Donald Trump and his apologists insist, of course, that race had nothing to do with his decision to send masked federal agents to Minneapolis and other cities, that he is only intent on upholding the law. But you will surely search in vain for a record of a non-Hispanic white person targeted for removal by ICE or the Border Patrol. Roughly 96 percent of the people ordered deported by this administration are being sent to nonwhite-majority nations.2

Indeed, Trump’s claim of racial equity in his anti-immigrant drive is undercut by his new program to make the path to American citizenship easier for only one group in the world: white people from South Africa. This is not, contrary to what Trump says, a humanitarian move to help Afrikaners escape genocide. There is in fact no systematic targeting of whites going on in South Africa, and no mass seizure of white-owned land, contrary to the right-wing talking points echoed by the White House. On the same day that the first group of five dozen Afrikaner “refugees” were personally welcomed to America by the U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, the Trump administration took steps to begin the deportation of thousands of Afghans — people of color — who had fled for their lives during America’s long war there.3

So the messaging is clear: America is for white people. It always has been, of course, but there was progress toward a reckoning with racism in recent decades — say, from about 1954, when a youngster named Cassius Clay started boxing, which coincided with the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which ordered an end to school segregation.

Unlike the young people of that era, though, children growing up in Donald Trump’s America don’t see their government pushing back against bigotry. I count myself lucky to have developed a political sensibility in the 1960s, as both the law and the social norms of my community delegitimized racism. Not everyone got the message, of course: My postal clerk, probably a decade and a half younger than I am, seems to have taken a different lesson from what he saw and heard than I did.

But there were signals throughout American culture during my youth that conscientious adherents of our nation’s principles wouldn’t tolerate the inequalities that had been long accepted before by even progressive Americans. The message came from the very top of our government.

In 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower sent 1,000 troops from the 101st Airborne Division, and federalized the Arkansas National Guard, to enforce integration of Little Rock’s Central High School. President John F. Kennedy likewise took control of National Guard troops in Alabama in 1963 to force the segregationist governor, George Wallace, to stop blocking the registration of black students at the University of Alabama. Acting on Kennedy’s agenda, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

To those who might claim those actions establish a precedent for Donald Trump’s military incursion into our cities now, let’s be clear: There’s no similarity between a symbolic show of strength to support constitutional principles, the tactic used by Eisenhower and Kennedy, and Trump’s malevolent deployment of a paramilitary force armed for urban combat to terrorize peaceful protestors, pull even lawful residents and American citizens from their homes in the night in defiance of court orders, and target journalists exercising their First Amendment rights.

It is tragic that those who might set an example of anti-racism are instead eagerly dismantling efforts aimed at bringing equity. What will a rising generation of Americans learn from this?

If you want to know what a society values, check what’s popular in the culture. In that regard, we may take a warning from this statistic: From 1995 to 2024, the top-grossing movie of the year was a violent film in all but six cases. Research analyzing scripts of 166,000 movies over five decades — from 1970 to 2020 — found that “murderous verbs” in dialogu e have risen steadily in all genres.4

It’s worth noting, then, that the most popular musical of the early 1950s was Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, which won both the 1949 Pulitzer Prize for drama and ten Tony Awards, then became a popular movie. It’s a tale set during World War II, but it’s not about fighting; rather, it is about racism.

South Pacific tells the story of an American nurse who falls in love with a French plantation owner, but struggles to accept his mixed-race children, with a subplot of an American Marine lieutenant who worries about the social consequences that would follow marriage to his Asian sweetheart. Prejudice is at the core of the work, most notably in the lyrics of the lieutenant’s song You’ve Got to be Carefully Taught:

You’ve got to be taught to hate and fear.

You’ve got to be taught from year to year.

It’s got to be drummed in your dear little ear.

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

You’ve got to be taught to be afraid

Of people whose eyes are oddly made

And people whose skin is a diff’rent shade.

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

You’ve got to be taught before it’s too late,

Before you are six or seven or eight,

To hate all the people your relatives hate.

You’ve got to be carefully taught.

The understanding of this dynamic, of course, underlies the Trump administration’s attack on schools and colleges — including its insistence on eradicating faithful examination of slavery, the near extermination of indigenous Americans and the obstinacy of racist anti-immigration sentiment throughout our history. The people who commit to teaching young people, who are often the targets of right-wing ire, tend to be deeply committed to truth-telling, with the hope that they might nurture a new generation of clear-eyed Americans.

It’s only by fully understanding the world beyond our own experiences and prejudices, after all, that we can hope to shape a better future for our country. But just now, young people are confronted with a message from their government, repeated over and over and bolstered by right-wing influencers and media outlets, that it’s better to suppress those who are different and who challenge the status quo — and that government is within its rights in using its might to take down those who protest its ways.

It’s that kind of thinking, of course, that laid the foundation for my postal clerk’s unexpected hostility to Muhammad Ali, who came over time to be honored for his acts of conscience, to the point of being immortalized on a postage stamp by the government that once prosecuted him.

We who see things differently from Trump’s agenda of hate need to do our part, then, to reach young people with a different message: that people should be respected without regard for their race or their beliefs, that all people deserve equal treatment under the law — especially those who hold the powerful government to account — and that it is our task as caring humans to welcome the strangers among us.

That’s the message that they’ve got to be carefully taught.

https://www.labxchange.org/library/items/lb:LabXchange:6fb7b7fd:html:1#:~:text=But%20extensive%20research%20on%20human,humans%20is%20not%20biologically%20real.

https://www.nbcnews.com/data-graphics/us-immigration-tracker-follow-arrests-detentions-border-crossings-rcna189148

https://www.npr.org/2025/05/13/nx-s1-5397007/trump-tps-afghanistan-afrikaner#:~:text=KQED,had%20relocated%20to%20the%20U.S.

https://www.arnoldpalmerhospital.com/content-hub/movies-are-more-violent-than-they-used-to-be#:~:text=A%20recent%20study%20in%20the,was%20first%20introduced%20in%201985.

WHY NOT TELL YOUR TRUTH?

LEARN TO WRITE OP-EDS — FOR PRINT, AUDIO AND PODCASTS

If you’d like some training in writing opinion essays — for newspapers, audio or digital platforms — check out the live 90-minute class Rex co-teaches that is offered by Marion Roach Smith’s global platform for writing instruction, The Memoir Project. Click below for information on our upcoming schedule of classes.

Our next class is WEDNESDAY, FEB. 18 at 5:30 p.m. Eastern.

Will you join us?

Lots of our students have been well published — and you can be, too!

BONUS CONTENT

GET MORE FROM THE UPSTATE AMERICAN

IF YOU’D LIKE TO HEAR MORE from Rex Smith, check www.wamc.org for his weekly on-air commentary aired by Northeast Public Radio. Here’s a link to the latest essay.

AND IF YOUR INTEREST IS SPECIFIC TO AMERICAN MEDIA, you can download the podcast of The Media Project, the 30-minute nationally-syndicated discussion that Rex leads each week on current issues in journalism. In the seven states where Northeast Public Radio is heard, the program airs at 3 p.m. each Friday and is rebroadcast at 6 p.m. Sunday. You can tune in live, too, at www.wamc.org, or download the podcast there. It has been called “a half-hour of talk about finding and telling the truth.”

WITH GRATITUDE

THE UPSTATE AMERICAN is a weekly essay aimed at helping all of us who are concerned about America’s future consider how we might best respond to the challenges of the day. Thank you for joining in the conversation about our common ground, this great country. I hope you’ll be back next week.

And don’t hesitate to send your thoughts, especially with ideas that you think we all ought to be considering.

-REX SMITH

Rex-

Thanks for another insightful article. The people of Minneapolis, Maine, and elsewhere subject to the brutal thuggery of ICE should give us all the courage to stand by our convictions. I remember well, as a child in the 50's, pulling out the LP of South Pacific from my parents' collection, and listening to it over and over. Those beautiful lyrics have lived with me ever since. Thanks for introducing them, in this fraught context and perhaps for the first time, to some younger generations of your readers.

Good on you Rex. We must resist hatred and racism firmly and with strength. It is the root cause of our current troubles.

“Nobody is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart; for his purity, by definition, is unassailable.” - James Baldwin